The world’s secrets are hidden inside silence

– Erling Kagge

What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence

– Ludwig Wittgenstein

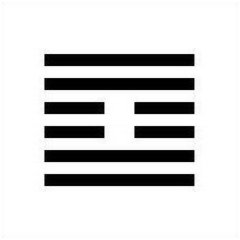

When you read the I Ching often, a particular hexagram will emerge. It might be the name of it, the text you read, or the symbol you sense and intuit. That varies for me but one of them is Inner Truth. I’ve spent some time with this hexagram.

According to Richard J. Smith in The I Ching: A Biography “in imperial China it was not uncommon for a scholar to spend days or even weeks contemplating a single hexagram.” Imagine a man in a robe sitting at a low wooden table. There’s incense, a painting on the wall, ink, pen, calligraphy and tea.

There was and still is a ritualised approach to the I Ching. There’s also a modern approach where you undertake a similar learning without ceremony. A hexagram becomes a mantra-like focus for the day, in quiet moments, or for study. It’s an energy pattern, symbol, and collection of words if you read a text. That’s not always necessary, because it’s the interpretation of others; but it’s advisable training.

Inner Truth tells you a great deal from the lines. This is potentially true of all hexagrams but with some it’s more apparent. Hexagrams are depictions of energy (qi or ch’i) in a structure of yang and yin. The Heaven trigram initiates, Earth receives then nourishes. The Mountain trigram either contains or inhibits, meditation as a positive practice but repression is negative. Lake collects then expresses energy, although more as a reflection than initiating force. Fire consumes energy, radiating it back in a different form. Water either flows or stagnates, in relation to a container. Thunder generates energy rising up from below, while Wind is the trigram of soft diffusion.

These energies become hexagrams with above and below, inner and outer connotations. The central lines of Inner Truth are soft yin surrounded or protected by hard yang. For hexagram 47, Oppression or Exhaustion, related words for this theme are “When one has something to say, it is not believed” (Wilhelm). This is a psychology of powerlessness and lost identity, described in The Divided Self by R.D. Laing. If you’re not recognised by other people, you can’t become yourself. But with earth food, water solvent, reasonable air and sunlight, a seed becomes a plant then flower or tree.

Inner Truth is a revealing hexagram for this process and how it extends beyond psychology. We might need yang armour surrounding yin vulnerability against hostile or uncaring environments. We might suffer a corrupt workplace, disrespect, or have the sensitivity of Wilfred Owen in war. You can’t encounter such things with yin; you must have outer yang.

Wilhelm explains “the centre of this hexagram is empty: this is its determining feature.” There are deciding factors in a hexagram, one of which is constitutional. The inside yin is not a dominating force but the tone or feel of it. Not leading, but the defining consideration.

Inner Truth as an idea relates to spiritual teachings and an identity beyond society. Environments condition, but we are ultimately spiritual thus not materially or socially defined. Inner Truth is like a map, corresponding to the model found in The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali:

| ….Line 6 | Wisdom | Dhyana, Samadhi |

| ….Line 5 | Authority | Dharana |

| ….Line 4 | Social consciousness | Pratyahara |

| ….Line 3 | Individual endeavour | Asana |

| ….Line 2 | Self interest | Niyama |

| ….Line 1 | Instincts | Yama |

It’s not an exact correlation, but Patanjali’s model describes a progression from selfish interest becoming spiritual realisation. There are components within each stage. Yama contains non violence (Ahimsa), truthfulness (Satya), non stealing (Asteya), and chastity (Brahmacharya). The latter seems odd with connotations of wrong doing, but applies in a meditation context where thoughts and corporeality are the problem. Nothing wrong with it, but not when you’re concentrating on a mantra.

Yama is what you avoid, becoming Niyama which is active discipline. Tapas, within Niyama, means austerity; not as self denial but making disciplined choices with long term consequences. Asana in one sense means the physical postures of yoga, some of which imitate animals. More subtly, Asana means inner attitude encountering outer reality. Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi describe the process of withdrawing from sensation (close your eyes and meditate) then the concentration which leads to spiritual culmination. Samadhi, the goal, is a similar term to yoga meaning union.

Selfish instinct becomes wisdom, and moral restraint becomes spiritual discovery. The six lines of a hexagram are six stages beginning then finishing. Inner Truth is the central area where lower meets upper, self meets external reality.

Hexagrams are linear, but also contain inside and overlapping layers. This is technical, which at this point is too complicated to explain. If you don’t understand, glean the general idea. The nuclear trigrams of Inner Truth are Mountain and Thunder. Mountain, in this context, concerns meditation with the top yang line a restraining factor above scattering yin thoughts. Thunder is below Mountain, because the constant activity of thinking is not easy to control. Patanjali describes yoga or union as “the cessation of the thinking principle.” In a book called The Voice of the Silence, by Helena Blavatsky, she advises “the mind is the slayer of the real.”

Truth is inside, not outside. I know nothing of the language, but the Chinese for Inner Truth is Chung Fu which I suspect is an alternate spelling for Kung Fu as the term for martial arts. But Kung Fu actually means “inner work” not exercising or fighting.

The baoti, or enveloping trigrams, apply to Inner Truth in the following manner. Yang Heaven encloses the top nuclear trigram of Mountain, and the lower nuclear trigram of Thunder. This a hexagram powerfully enclosed by yang, within which internal work occurs. Visually, and energetically, we are drawn to the central empty space where the lower and upper trigram engage.

These ideas converge as a simple principle, having established the complexity of the terrain. The poet John Keats called it negative capability. He described it in a letter: “to accept uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” This is how we consult the I Ching. It’s a receptive, reflective, and intuitive practice. The empty space at the heart of Inner Truth is where negative capability is found.

Kathryn Schulz in Being Wrong: Adventures on the Margin of Error considers the subject in several areas. There’s sensory fallibility, intellectual knowing or not, belief, evidence, certainty, and how these express in society. She says “this book has been devoted to bringing to light the good side of error: the lessons we can learn from it, the ways it can change us, its connection to our intelligence, imagination, and humanity.” It’s a significant claim, consistent with spiritual teachings which advise we don’t know, as the basis for knowing.

Seeking quietness within the noise of civilisation is a fine pursuit. In addition to not knowing, there is a quality of quiet at the heart of Inner Truth. The context is different, but the words poignant, in the early part of Evelyn Waugh’s novel Brideshead Revisited:

It was as though someone had switched off the wireless, and a voice that had been bawling in my ears, incessantly, fatuously, for days beyond number, had been suddenly cut short; an immense silence followed.

I write like this is a magazine column. With research, references, and a lot of time. If you like it, perhaps you would support me.