The future is real, the past is all made up. Everything everywhere is always moving forever

– Logan Roy, Succession

We should let history illuminate thought, but we also should let thought illuminate history

– Chung-Ying Cheng, The Primary Way

Why do we like mafia drama? Scorcese’s films are best sellers and we are fascinated with Don Corleone, Don Pietro, Tony in The Sopranos. In Goodfellas, Henry Hill gives girlfriend Karen a gun to hide and she says “I must admit, it excited me.” There’s a clue: it’s about power.

In The Godfather Michael Corleone says “so who’s naïve now?” to wife Kay, equating the mob to governments. She suspects his activities and doesn’t like it. Organised crime is different from government, but we feel sympathy with the idea. No one likes being bossed around or controlled and we all feel, at one time or another, society imposes on our freedom. No one messes with the mob.

In Gomorrah we see the workings of the mafia more clearly, described as “the system.” It means a network of drugs, gangs, bosses, families, payroll politicians and apparently respectable business where crime money disappears. There’s a parallel here with the television series Succession. That concerns a media empire not crime, but with another family portfolio. Television, newspapers, internet, a theme park, and luxury cruise liner. Logan Roy is like a Don. He plays a game on his birthday which means flying over cities at a whim, helicopter always ready. In Gomorrah, Don Pietro raises a riot in prison then theatrically raises his hands to show his control. The first demonstrates vast wealth, the second mob influence: both are displays of power.

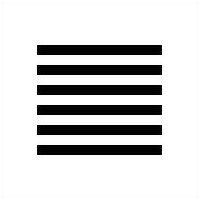

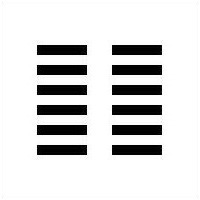

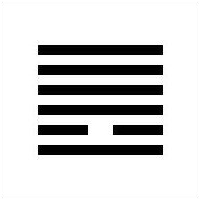

Power is often unethical. But in a Taoist context, it’s different. It corresponds to consciousness, being, and spirit. The Tao of Power by R.L. Wing clarifies the idea. The I Ching begins with power hexagrams, Heaven the source and Earth the container. The book concludes with After Completion and Before Completion, hexagram 63 the perfect balance where “The transition from confusion to order is completed, and everything is in its proper place” (Wilhelm). The book can be summarised with those four hexagrams. Power and polarity begin, change, and blend. Although there’s no conclusion, because change never stops.

There is more commentary for the first two hexagrams than others. Studies were perhaps lost, a thousand years ago; or perhaps people knew their importance and wrote more extensively. With such an ancient book, we don’t have all the facts. Wilhelm spoke of nuclear trigrams called hu but not enveloping trigrams called baoti. The baoti are less known. They have a different structure and meaning, as a controlling or limiting influence. That could be unconscious feelings which inhibit a plan, or a constraining situation. You can emphasise the baoti for a reading, use the more familiar hu, or both.

The first hexagram is the beginning of power. It’s a sleeping dragon, which awakens and acts. We are told he hides, appears in the field, flies in the heavens, then finally is arrogant. The top line of a hexagram is leaving a situation or the beginning of decline because “by the law of change, whatever has reached its extreme must turn back” (Wilhelm). Leaving and decline are energetically similar, but with a different meaning.

The first hexagram Ch’ien means the Creative, or Heaven, and consists of yang lines in a sequence. The lines don’t particularly correspond, two with five for example, because they are constitutionally the same. Meaning is derived from place more than relationship. The idea is when yang and yin occur they relate, but the first two hexagrams are different.

|

|

The lines advise “do not act” then “the superior man learns in order to gather material” and “he questions in order to sift it.” This is power used strategically. “All day long the superior man is creatively active” then “at nightfall his mind is still beset with cares.” There’s no rest, because yang is power not repose. The hexagram speaks of advance, retreat, and the need for perseverance according to “one’s nature.” We must “do everything at the right time” according to six stages of development. The six stages apply in all hexagrams, clarified in the first.

Ch’ien could be read as Machiavellian advice. But you can’t use the I Ching for bad reasons. The structure is of light and dark, day and night, good and bad, with warnings about evil. Although it’s not a book of belief, so comparable in that respect to the Upanishads or Tao Te Ching. It’s a description of the universe which is ultimately good, sometimes obscured with evil. The hexagram Ming I means Darkening of the Light. It’s appropriate for the mood of society when we encounter war, illness, and threat because “The light has sunk into the earth: Darkening of the Light” (Wilhelm).

Gangster drama is a thrilling watch because we see the operation of power, although it’s corrupt and entrapping. Power itself is the ability to do something, not an indication of light or darkness. The Taoist I Ching by Liu I-ming, in particular, describes a universe where light battles with darkness in the sense of consciousness overcoming conditioning: “The quality of strength in people is original innate knowledge, the sane primal energy” (hexagram 1).

There is a gender dimension where the mob is usually but not always male. It’s true for The Godfather of some years ago, not in the recent Gomorrah. Scianèl is unpleasant because she is sadistic. Patrizia is likeable. We see her as a family provider, she has to endure Scianèl, then her defiance of Don Pietro becomes mutual trust. Her story begins with injustice she doesn’t forget. This is similar to Michael Corleone’s paternal love changing to loyal action: “I’m with you now Pop” he says in the hospital, understanding him when others try to kill him.

Anyone can be evil, irrespective of gender and politics, but there are poignant gangster moments and we feel some people are better than others. We like Tony Soprano (he cries watching his daughter sing in a concert) but not Richie Aprile. In The Godfather, Kay wants to be with her husband but is shut out of the darkened room, with a closing door, as senior mob kiss his hand. In Gomorrah, Patrizia finds herself a liability in circumstances she didn’t create, and Genarro kills her in a planned second. Their world is one of power not love. In this respect it fits the category of tragedy when people want to escape but cannot. “Just when I thought I was out” says Michael Corleone “they pull me back in.” He never forgets Apollonia, whom he marries in Sicily.

After trying to kill each other Gennaro and Ciro finally love “Brothers in Arms” as the Dire Straits song says. They fight together, with the ghost of Don Pietro structurally alive. Gennaro is damaged when his father disowns him. He’s not a son but a threat, liability, competitor. “Women and children can afford to be careless” says Vito Corleone “but not men.” It’s a logic both tragic and violent when Michael was responsible for Apollonia’s death. The car bomb was intended for him, not her, and there is nothing worse than destroyed Ophelia-like innocence.

The mob call themselves soldiers and their ruthlessness compares. Hexagram 7 is The Army. Wilhelm advises “The rulers of the hexagram are the nine in the second place and the six in the fifth.” According to Wang Bi, an influential interpreter of the I Ching, lines two and five are notably important because trigram centrality corresponds to the mean. It’s like chess, with a strategic placement influencing others. Structurally, the two is strong yang within common society. A charismatic person, connecting to above five which is like the church in The Godfather. Respected establishment, but as corrupt as the mafia. They make claims like a business scam, never proving it but here’s the collection box. An idea in mass circulation becomes a unifying nucleus for action. An army relies on a common purpose. Without that, there is no army.

The structural opposite of The Army is hexagram 13 called Fellowship With Men. Wilhelm explains it:

The Creative acts. Order and clarity, in combination with strength; central, correct, and in the relationship of correspondence: this is the correctness of the superior man. Only the superior man is able to unite the wills of all under heaven.

Uniting here is for good not bad; albeit armies are ethical against evil. The important second line in Fellowship is yin not yang, receptive not active, which avoids the tragic structure of hubris and hamartia. Push too far, assume too much, think you have the answers, and fate will teach you a lesson. This is a constant I Ching theme. The book is abstract, but correlates with Confucian ideas of social harmony. In The Doctrine of the Mean, Mencius connects above with below:

When all beneath Heaven abides in the Way, small Integrity serves great Integrity, and small wisdom serves great wisdom. When all beneath Heaven ignores the Way, small serves large, and weak serves strong. Either way, Heaven issues it forth – and those who abide by Heaven endure, while those who defy Heaven perish.

The difference here is a decent society where integrity and wisdom operate, compared to a politics society where power is the only meaning.

Fellowship does not mean everyone is the same. This is not an ideal about brotherhood and sisterhood as an overriding or universal sentiment. Even in the mob, differences occur. Thus “the superior man organizes the clans / And makes distinctions between things.” We recognise commonality, but the superior woman or man “must not degrade himself. Hence the necessity of organization and differentiation.”

Hexagram lines are stratified as a reflection of psyche and society, philosophical above and prosaic below. Order against chaos is an important I Ching theme, and worries should be contained. Psychologically we need edges and boundaries, so night doesn’t flood day.

I write like this is a magazine column. With research, references, and a lot of time. If you like it, perhaps you would support me.