There seems to be such a thing as beauty, a grace wholly gratuitous.

– Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

We have formed a firm decision that Odysseus has waited long enough. He must go home.

– The Odyssey

There’s a difference between the I Ching system and what people write about it. The first means the symbols which were originally an oracle. The second refers to the books where interpretations are provided. Wilhelm thinks and writes philosophically, which is not always directly relevant for a question. His words are like stories, based on the symbols, you then apply for yourself.

In film and literature there are narrative patterns as there are in the I Ching. Some of them trace back to the Iliad and Odyssey. Achilles is the angry warrior, needed in battle, persuaded to return. Deckard in Blade Runner is not angry but retired. His expertise is also needed. In Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain, W.P. Inman undergoes a long challenging trip returning to his love, Ada Monroe. In The Odyssey, Odysseus returns to Penelope. Men fight and might die to reach a waiting woman. This is reconfigured in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon with female fighters Jen Yu and Yu Shu Lien; in His Dark Materials (by Philip Pullman) with witch Queen Serafina Pekkala. “What can you do?” a child asks her. Witch magic is what she does.

I Ching symbols are read intuitively, or with philosophy and learning. You can use trigram energies as the basis for a reading, separately from books. This is the approach of Harmen Mesker who doesn’t trust the veracity of translations, and applies his Chinese learning to decode ancient texts. But English versions are like reading Spanish or Chinese poetry. We know it’s not the original, and read suggestively not precisely.

The structure of the I Ching functions with philosophy. It means nothing without it. Translator C.F. Baynes, who rendered Wilhelm’s German into English, was indebted to Carl Jung saying “one very real compensation for my lack of Chinese remained, namely, the access to its philosophy afforded me through my growing knowledge of the work of Jung. This gave me a key to the archetypal world of the I Ching.” It’s not an exact fit with Chinese philosophy, Taoism in particular, but the Jungian sensibility is an essential part of a modern reading.

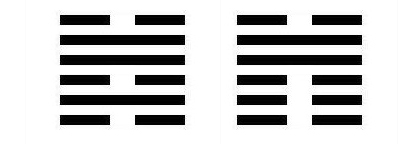

In Jung’s foreword to Wilhelm’s book he enquires about the nature of the I Ching and receives hexagram 50 called The Cauldron. Within the book we find “wise counsel and deep insight” consistent with Depth Psychology. At a personal moment when I was feeling powerless, desperate, and beaten by hostile forces I thought of hexagram 47 called Oppression and Exhaustion. Wilhelm describes how it makes no difference what you say, as a description of depression internally and power relations externally. Psychologist Martin Seligman describes this as “learned helplessness” with a feeling of permanence, pervasiveness, and personalisation. When social relations are defined with power, not respect, it is useless trying to reason.

I consulted Exhaustion wondering what needed to change and the Water trigram below, called The Abysmal, was the problem. The Lake trigram above is called The Joyous meaning happiness, but as a potential not necessarily the reality. I felt I needed the element of earth to absorb water so I could feel substantial not fluidic. When Lake below changes to Earth, hexagram 45 is the result called Gathering Together. The change occurs not with power or action, which is not the feeling I had with hostile people, but with increased yin meaning acceptance and self focus. Care for me, try not to worry about unpleasant others because “In this way we are equal to every situation, because we accept its meaning without resistance” (Wilhelm commenting on a section of the Ta Chuan).

In the evening, I watched a film about a man describing his teaching career in which managing expectations was a critical factor. This was synchronicity. If you can’t reason with someone you lose power when you engage thoughtfully, expecting the same. You can’t discuss poetry with a rock. This explained the situation and Wilhelm provided a wider philosophy. He writes “The gathering together of people in large communities is either a natural occurrence, as in the case of the family, or an artificial one, as in the case of the state.” This describes the difference between care and power as the yin and yang of society.

Symbol knowledge of trigrams derives from the Shuo Kua, which is part of the Confucian Ten Wings. My experience with hexagrams 50 and 47 was based on reflection, not throwing the coins, with a secondary consideration of trigram energies. Harmen Mesker describes them as easily understood ideas for which Earth, Lake and Water were important:

Heaven: action, movement, masculine, father initiating.

Earth: receptive, open, mother, nurturing, passive.

Lake: cheerful, relaxed, creative, positive.

Fire: warmth, clarity, insight, finding meaning in something.

Wind: curiosity, flexibility, gentle penetration.

Mountain: rest, meditation, quiet and unwavering.

Water: unconscious, hidden, fear, doubt, risk and danger.

Thunder: fierce energy, new beginning, spontaneous, fast and direct.

If I’d approached the I Ching beginning with trigram symbolism, I wouldn’t have made the psychological connections. Meaning started with a large concept, the idea of Exhaustion, not component parts of a hexagram. Managing expectations was the central point, and I wondered about further reading. Nietzsche is my favourite Western philosopher but that’s not his subject. Indeed, his ideas might be scrutinised in terms of idealism and reality. I considered Stoicism, and found a remark from Epictetus: “Seek not that the things which happen should happen as you wish; but wish the things which happen to be as they are, and you will have a tranquil flow of life.” Tranquil flow is not the immediate outcome for threatening circumstances. It does however describe the wider subject, illuminating a specific encounter with philosophy.

In The Primary Way, Chung-Ying Cheng emphasises the philosophical quality of the I Ching which is not confined within the system. We don’t always need it, and might understand a situation in I Ching terms without noticing. We sense for example, the need for a trigram energy such as vigorous exercise (Thunder) or a calming hobby like gardening (Earth). Exhaustion was the archetypal situation I recognised within myself before consulting the I Ching.

Feeling powerless and undervalued corresponds to the Chinese element of Metal. Gold is valuable, because it is rare, like the unique worth of individual people. In Chinese philosophy and medicine Metal is the element of autumn, and for the I Ching means the trigrams Heaven and Lake. Trigrams, and hexagrams, operate with a seasonal correspondence. The I Ching is nature based, extrapolating from the planet where we live into deeper principles. In Anatomy of Criticism, literary critic Northrop Frye describes stories of spring, summer, autumn and winter. Spring and autumn are seasons of change connected to comedy and tragedy. Summer is utopian, the opposite of dystopian winter:

Spring: comedies, when bad situations have happy endings, such as Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.

Summer: utopian fantasy, as with J.L. Carr’s A Month in the Country

Autumn: tragedies where ideal situations disintegrate, as with Hamlet and King Lear.

Winter: dystopian tales such as Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

In David Hinton’s I Ching he refers to the interpretation process, seasons, and what this means for the first hexagram:

The graphs may be a list of the essential characteristics defining the four seasons. Hence, assuming heaven is part of the sentence: Heaven is birth and flourish, harvest and completion. But the graphs are usually given a more philosophical cast. For 元, the range of meanings might also include: origin, generative impulse, great, awe-inspiring; for 亨: penetrate, develop, success, prevalence; for 利: bounty, fitness, profit, effective; and for 貞: inexhaustible, constancy, upright and true, righteous.

This complex remark is essentially a simple idea. In the first hexagram (and throughout the I Ching) the seasons are recognised as important energies.

Natural cycles shape the flow of life, featured in the I Ching but not confined to it. There are archetypal connections between literature and the ancient book. Summers of childhood live in memory as long and idyllic. A time of carefree contentment, never again captured, which is the theme of Alain Fournier’s novel The Lost Domain (Le Grand Meaulnes). Nostos is the term for this, the basis of the word nostalgia meaning longing for the past. Return is how you reach the past. It’s gone, although you remember it, and the final scene of A Month in the Country is elderly Tom Birkin reflecting on his countryside summer.

Return also has spiritual significance. In chapter 16 of the Tao Te Ching the word repeats:

Empty yourself of everything.

Let the mind rest at peace.

The ten thousand things rise and fall while the Self watches their return.

They grow and flourish and then return to the source.

Returning to the source is stillness, which is the way of nature.

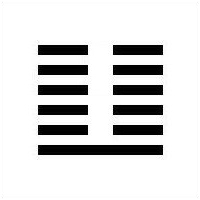

In this context the ten thousand things means the distraction of thinking in meditation. Return means finding the stillness you’ve lost. The I Ching is used for daily questions, but a spiritual framework underlies it. With the Tarot system Major Arcana cards are spiritual and philosophical, while the Minor Arcana describe mundane affairs. The I Ching begins with Heaven and Earth hexagrams representing spirit and matter. Subsequent hexagrams express this polarity in different circumstances. Return is the name of hexagram 24 where we read:

After a time of decay comes the turning point. The powerful light that has been banished returns

The idea of Return is based on the course of nature. The movement is cyclic, and the course completes itself.

A man is in a society composed of inferior people, but is connected spiritually with a strong and good friend, and this makes him turn back alone.

Meaning is elevated and philosophical with Wilhelm. This is why his book is highly regarded, as you receive answers and something more. Yin is the quality of Return because of five yin lines, but yang entering from below is the directive. In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (C.S. Lewis) witchcraft is evil. At the end of the book, Aslan returns after apparent death because:

Though the Witch knew the Deep Magic, there is a magic deeper still which she did not know. Her knowledge goes back only to the dawn of time. But if she could have looked a little further back, into the stillness and the darkness before Time dawned, she would have read there a different incantation.

Translators describe a cognitive experience which is not one language or the other. They think differently, with differing words, operating from pre-verbal perception. There’s something similar with the I Ching. It’s not entirely a textual or imagery system. Reading words, and pondering the symbols, stimulates intuition from both directions.

In David Hinton’s I Ching he describes the language of the book as a reflection of its essence:

This mystery of things was seen from early times as a kind of silence, an absence of linguistic knowing, and it was considered the deepest wisdom.

I write like this is a magazine column. With research, references, and a lot of time. If you like it, perhaps you would support me.