The child is innocence and forgetting, a new beginning, a game, a wheel rolling on its own, a prime movement, a sacred Yes

– Friedrich Nietzsche

This is not altogether Fool, my Lord

– William Shakespeare

If you want to advance with the I Ching, read and study it separately from questions. Then when you ask a question, your understanding is improved. In the introduction to Thomas Cleary’s book The Tao of Organisation (translating Cheng Yi) he suggests an interesting method. Read two hexagrams every day for the entire book. Read it again, while noting the following: what interests you, what pleases you, what flatters, insults, disturbs, accuses and exposes you. He says “look at immediate reactions first, then look at deliberate thoughts.”

This is literary training. I taught English for a short time and the basis for it is encouraging a personal but critical response. You have a feeling about a poem but must calibrate and contextualise what you write. It’s your subjectivity, not that of others. I remember my first Sixth Form essay about King Lear. It was covered in red ink, tearing it apart, advising the same: say why, explain, and be critical. I was dismayed and then confused when the teacher wrote at the end, get this right and you will do well, because your style and response is impressive. It wasn’t a good school to put it mildly. There were however some good teachers, my King Lear essay was a formative moment, and I achieved an A grade A Level.

Cleary continues, advising you look for “specific qualities in specific conditions” then “the relationships found between corresponding lines.” It might be leadership for example, which applies for King Lear. Kingship means leadership, in which respect Lear is lacking because he doesn’t understand the politics of selfishly conflicting intent. He feels betrayed when two of his daughters are only interested in their portion of the kingdom he gives away. They don’t respect him. When I was training for my English PGCE (FE) I remember another good teacher offering advice. Teach King Lear, he said, with the opening idea that it’s a family argument. The average sixteen year old starts listening.

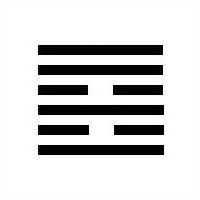

These dynamics, and many more, are found in the I Ching. The Family is hexagram 37 where “The influence that goes out from within the family is represented by the symbol of the wind created by fire.” The upper trigram is Wind and the lower is Fire.

In the Shakespearean world, and with Confucian advice, disorder in one place reflects in another. Lear claims he is sinned against. But it is his responsibility as King to encompass those below him. He should know the character of his daughters. He may have done, but now he is old; so it’s a complex subject. Wilhelm advises “the superior man has substance in his words and duration in his way of life” which Lear doesn’t have.

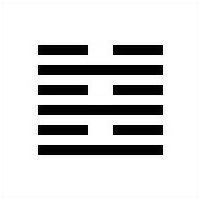

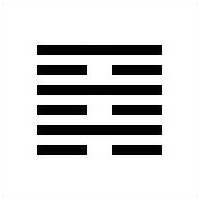

The idea of return is a repeating theme in film and television. In Gomorra, the gangsters Don Pietro, Gennaro Savastano and Ciro in particular are overcome by others, imprisoned, nearly killed, then return. Hexagram 24 is called Return. Lear’s clarity returns when he properly recognises Cordelia, but as tragedy not healing. Hexagram 63 is a structurally perfect moment of yang and yin. But it doesn’t last, when 64 is the following opposite, just as Lear and Cordelia unite but then die.

|

|

Fellowship With Men is hexagram 13 where Wilhelm says “the superior man organizes the clans and makes distinctions between things.” This is perfect advice for Lear. In The Forest of Changes by Jiao Shi Yi Lin, at line 3 of hexagram 13 he advises “The floodwaters recede, the perfected man is hidden. Use weeds and brambles for pillars and beams, and the house is bound to collapse.” Lear has lost the dignity he once had (we assume) as a king. His metaphoric house collapses. His lowest moment is when, driven mad with what people are doing to him, he rages at a storm.

Cleary encourages a literary I Ching understanding which I also recommend. He says “those interested in the implications of a strong leadership may further refine their perceptions by studying the leadership from the point of view of its relation to its inner correspondents in the lower echelons of the organization. They would turn to the middle lines of each hexagram to find the relevant combinations.” I do that here with central trigram lines.

A King rules at line 5. His subjects operate below him. Line 6 above, in King Lear, is The Fool. Comedy is a social role where you tell sharp truths and get away with it. The Fool advises Lear which annoys him but which is correct. In The Comedy of Survival: Literary Ecology and a Play Ethic Joseph Meeker explains how laughter is more profound than tragedy. Forget Lear and Hamlet, or at least balance them, with a reading of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

We were advised in the Sixth Form to learn quotations for the exam. Sue Upton (I needed thirty minutes to remember her second name) was in the class. I’ve got one she said: “Out, vile jelly!” and we laughed at the line which in reality is an horrific moment of blinding. That’s not an amusing joke for adults when we know the reality of cruelty. Sue didn’t, so it was funny, consistent with Aristotelian catharsis and the innocence of the young.

I’ve been applying Cleary’s advice for years. Not the basics of likes and interests, but correlating the I Ching with literature and philosophy. It’s the same approach, at a more sophisticated level where the basics are contextualised: “look at immediate reactions first, then look at deliberate thoughts.”

Cleary is an interesting writer. He says Cheng Yi was “a distinguished educator and activist of eleventh-century China, noted for his role as one of the founders of the movement known as Lixue, or study of inner design.” In another of his books, he makes the claim that King Wen and the Duke of Chou (authors of core I Ching text) were taught by a Taoist sage. He encourages the literary method, but also explains a Taoist method where you don’t read the books. This is my dual approach. It’s a great loss if you don’t read Wilhelm. Simultaneously, the important thing is the structure of the hexagram and how that applies in different circumstances.

King Lear is male and powerful thus (flawed) yang, his daughter Cordelia is yin, and the tragedy in this respect is his inability to recognise innocent powerless love. It’s not about words which are “that glib and oily art / To speak and purpose not.” Thus she answers his question simply with no ornamentation: “I love you according to my bond.” Lear hesitates, then berates her for insufficient language. Goneril and Regan use the rhetoric of politicians and with them, mistakenly, he is content. He banishes Cordelia, reunites with her at the end of the play, but it’s too late.

Hexagram 25 is called Innocence and The Unexpected. The yang trigram is above which represents the King. The play is about Lear, what he represents, the power he potentially carries, but how he lacks understanding for which hamartia is the Aristotelian term: “to miss the mark” or “to err.” The lower trigram of Innocence is Thunder, or shock, representing the knowledge Lear has to learn as a painful experience. He finds Cordelia again but she dies; he dies from a broken heart.

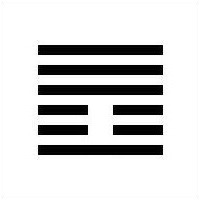

Wilhelm advises “If someone is not as he should be, he has misfortune and it does not further him to undertake anything.” There are two dimensions to innocence. The first has a correspondence to Youthful Folly (hexagram 4) when a beginner, novice, or young person has to learn about the world. Working knowledge is external, not yet inside them, albeit that might be knowing about corruption as it is for Lear. Confucianism speaks of virtue (ren) and what in effect is sociology and ethics. This is partly the struggle of King Lear.

The second dimension of innocence is subtle and Taoist. Cordelia, misunderstood as she is, symbolises something transcendent and simple. She loves innocently, it’s not returned, but doesn’t stop loving. There’s a description of trigrams designating them eldest, middle, youngest son and daughter. They derive from Heaven and Earth, as the rising and falling of yang and yin. The youngest daughter trigram is Lake, a yin line above two yang lines. Cordelia is the youngest daughter. Lake means joy, calm, and serenity.

Referring to trigrams, Cleary advises:

The relative positions of lower and upper are regularly associated with various social and psychological phenomena exhibiting analogous patterns, such as leading and following, or patterns analogous to the inner/outer contrast, such as home/ work, psychological/social, individual/group.

Structurally, the emphasis of King Lear is the King and his psychology, where a typical essay question is: “I am a man more sinned against than sinning” says Lear. Discuss. I have never seen a critical discussion of Cordelia’s innocence and what it represents. It’s an idea with lesser importance, because her presence in the play is minimal. She’s there briefly at the beginning and end. But her absence is a silent theme, her return the conclusion of the play. For the I Ching, Innocence has its own hexagram and Wilhelm advises “Under heaven thunder rolls: all things attain the natural state of innocence.”

I write like this is a magazine column. With research, references, and a lot of time. If you like it, perhaps you would support me.