From a small seed a mighty trunk may grow

– Aeschylus

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown

– William Shakespeare

My first political vote was for a Green party as a protest against the principle two. The second was a vote for a main party, opposing the other, which had become extreme. They were like Sixth Form debaters. Sophistication and reality were lacking. If they were elected, I read, Britain would be in serious trouble. I dislike politics thus have voted only twice.

Studying Shakespeare at university, I described his plays as timeless wisdom in the category of art. That’s wrong, my tutor said, because he was a product of time and place. I didn’t agree and don’t now. We might have discussed it further although it was intuition at that age more than learning so would have achieved nothing. He was politically very left. Which means, as far as literature is concerned, a rhetoric of cultural construction.

The same occurred in a Sociology lecture about Karl Mannheim. Knowledge is socially constructed, he said, which is an irritating claim because it means you cannot transcend conditions and are judged for whatever you say. Your personal becomes their political, which is extraordinary arrogance. It was around the time I bought my first I Ching, Tao Te Ching, Bhagavad Gita, and was reading about Karma, Bhakti, Jnana and Raja Yoga.

I recognise the partial validity of my lecturer regarding socio-political influence, but Shakespeare and as we might also say E.M. Forster, Cormac McCarthy, Haruki Murakami and Ian McEwan cannot be reduced to politics. The I Ching is not politics. “There are more things in Heaven and Earth” Hamlet says “than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” That is a timeless statement in relation to arrogance, known, and unknown.

In comparison to university, my A Level experience was balanced. In the first Sociology lesson we were introduced to Conflict Theory (Marx) posited against Functionalism (Durkheim) which we evaluated in an essay. I don’t know what other students wrote. I said that both are partially true.

Nietzsche explains university bias as ressentiment. He was interested in deeper structures which extend to the Greeks, religion, and psychology. Critical theory is interesting as a form of intellectual training. I pursued it in fact, reading a little, when it wasn’t part of my degree. But it becomes a voting ideology devoid of greater meaning.

Politics produces a distorted vision of the world, organising experience into tribal schemata which are not relevant for normal living. We want ordinary normality (certainly I do) some of which depends on who is in power but that has no bearing on what we read, the partners we have, hobbies we pursue, with the motivations of pleasure, security, and satisfaction. In 1984, Winston Smith finds comfort in a relationship with Julia.

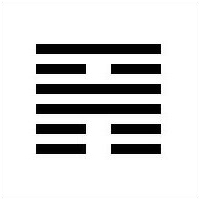

I’m not a politics person. I’m a thinking, nature, walking, reading, photographing I Ching person. Ideological attitude means, I now realise, there’s not much discussion possible. My lecturer wrote Marxist books as a leading Shakespearean scholar. I have no interest in failed discussion (read Wilhelm’s hexagram 47) except to point out, perhaps, how ideology as a source of meaning is questionable. A few years ago he had life threatening problems with his heart. Marx doesn’t address that. I wandered the library seeking Taoist, yoga, and Buddhism books. This is hexagram 56 called The Wanderer:

As with many subjects politics can be understood with the I Ching. You can use hexagram analysis to describe personality according to this model:

| ……….Top line | Outer reason |

| ……….Fifth line | Outer human feeling |

| ……….Fourth line | Outer desire |

| ……….Third line | Inner reason |

| ………Second line | Inner human feeling |

| ……….First line | Inner desire |

Desire is an expression of vitality, which can be selfish although to varying degree. You may desire a home, companion, food, which is entirely innocuous. Human feeling is an expression of energy, when the forces of desire and reason are mixed. It’s the area of literary criticism. Reason is an expression of intelligence, which may be coherent or not as the exercise of philosophy.

Someone who is inwardly angry (1) motivated by resentment (2) who rationalises this (3) with an appearance of concern (4) pertaining to society (5) with idealism (6) means yin in the lower three places and yang in upper places. This describes an ideological personality. It explains the horrors of Stalinism when means were used to justify the end.

There’s an entertaining book by comedian John Cleese talking with psychologist Robin Skynner. They correlate political character with psychology in dialogue form:

John: One British political correspondent told me that the politicians he knew were with very few exceptions vastly more vain and pompous than average people. Do you think our present system encourages this – that people get involved in party politics as a way of avoiding questioning their mental maps, and staying inflated by feelings of omniscience?

Robin: Yes, I think many do. The best and most healthy probably have a desire to serve the community without too much of a hidden agenda. They’re not mainly seeking something for themselves and they don’t take it all too seriously. But I believe that people operating on passionate belief, who are very keen to change other people – whether it’s stopping people hunting and shooting, or making others work harder for less money – have opted for changing the world so that they don’t have to change themselves….

John: You mean, they use their political views to give themselves a stronger feeling of identity?

Robin: Yes, as a prop to support themselves. Whereas truly confident people don’t need to hold on to views so tenaciously – they’re much more comfortable about constantly revising them…

John: You mean, instead of trying to find things out, they start trying to prove that they are right? (Life And How To Survive It, 1996)

Cleese and Skynner decide, talking together, how nonsensical it is speaking of utopian change when advance occurs over many years. Not within the discharge of one government, but as a slow Hegelian process which includes culture. Policies can be implemented or removed but it’s not a wondrous event when a party assumes power with grandiose claims. What happens is they lose energy, everyone gets bored, then the other side returns.

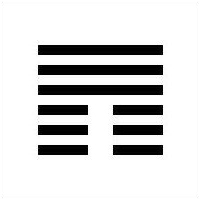

Three yang lines above yin produce the hexagram called Standstill or Stagnation. Advance is possible with decent government but the hexagram is more subtle. It means, in a deeper context, if you believe in politics as such you will get nowhere. Wilhelm advises “This hexagram is the opposite of the preceding one. Heaven is above, drawing farther and farther away, while the earth below sinks farther into the depths. The creative powers are not in relation. It is a time of standstill and decline” because “The great departs; the small approaches.”

Friedrich Nietzsche is an interesting comparison. He’s one of the truly great thinkers, making structural observations about preceding philosophy. Tragedy for example is one of his interests, the literary form of Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles. It’s also a philosophical form with connections to religion. The premise of both is we are subject to greater forces, and reality itself, we neither construct nor control. Nietzsche disliked Christianity because (he said) it weakens people with notions of sin and subservience. He was more generous with Buddhism:

Buddhism is a hundred times more realistic than Christianity – its body has inherited the art of posing problems in a cool and objective manner, it came after a philosophical movement that lasted hundreds of years, the idea of ‘God’ had already been abandoned before Buddhism arrived. Buddhism is the only really positivistic religion in history; even in its epistemology (a strict phenomenalism) it has stopped saying ‘war against sin’ and instead, giving reality its dues, says ‘war against suffering’. In sharp contrast to Christianity, it has left the self-deception of moral concepts behind – it stands, as I put it, beyond good and evil (The Antichrist).

In Christianity you never become the origin of the universe yourself. In Buddhism there is no “God” but rather states of consciousness culminating with nirvakalpa-samadhi which means union with no-thing. I agree with Nietzsche that “Buddhism is a religion for mature people” insofar as the philosophy is more developed.

Nietzsche regarded Thus Spake Zarathustra as his greatest work, and it was a representation of himself. It wasn’t however the reality of the man, and the life he lived, which included suffering and illness. According to psychologist Alice Miller in The Untouched Key, early life neglect was the basis for his philosophy of overcoming. When Nietzsche Wept is a startling idea and the title of a novel by Irvin D. Yalom. Freud becomes the source of insight, greater than the philosopher himself. But Nietzsche knew his frailty alongside his intellectual power thus “we are human, all too human” was his reminder.

The inner desire of Nietzsche (1) was knowing, in regard to life struggles and the deficiencies of earlier philosophy. His motivation was overcoming (2) as an idealised but elevating proposition consistent with Jungian Individuation. He rationalised this (3) with a Superman idea, excoriating belief systems of never knowing. He wasn’t overbearing in his personal life (4) as you might imagine, but dependent because of illness. He needed community (5) like every other person. He was idealistic in his words with a fearless insistence on accurate thinking. But he did weep (6) when he saw cruelty inflicted on an animal, emblematic of fierce enquiry broken with a final admission: we can’t overcome, so we suffer, because tragedy is ontology.

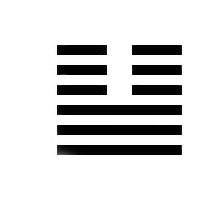

This hexagram analysis for Nietzsche is three yang lines below three yin, called Peace. Wilhelm advises “The Receptive, which moves downward, stands above; the Creative, which moves upward, is below. Hence their influences meet and are in harmony, so that all living things bloom and prosper.” This is not correct in regard to Nietzsche’s personal life. It is for his philosophical struggle, Zarathustra bringing mountain wisdom into society.

“We know what we are but / know not what we may be” are beautiful words spoken by Shakespeare’s Ophelia. I taught children for two years with memorable moments. “The comfort of my imagination” was what a child wrote about a book she’d read. The Ophelia lines were what I wrote, above a large tree, painted on canvas, hung on a wall, which children decorated with green leaves and words of their own.

I write like this is a magazine column. With research, references, and a lot of time. If you like it, perhaps you would support me.