What is above form is called Tao; what is within form is called tool

– Ta Chuan (The Great Treatise)

The Chinese philosophy, on the other hand, takes change and transformation as ultimate reality and truth. This of course bespeaks of the uniqueness and essential importance of Yijing and its philosophy

– Chung-Ying Cheng, The Philosophy of Change

It’s worth remembering I Ching means Book of Changes. It’s what initially attracted me. I bought my first copy as an undergraduate, with a Tao Te Ching. I still have them alongside different versions I’ve acquired. They are still probably the best, by Wilhelm and Gia-Fu Feng. The I Ching is a book about change.

Wilhelm’s book is distinctive, but wider reading is valuable. I found Stephen Karcher a few years ago, and he makes an interesting contribution with a Depth Psychology approach. He’s a Jungian, blending the ancient book with contemporary understanding. Although that can be reductionist, when Taoist ideas are reconfigured as archetypes. Freud famously said a cigar is sometimes a cigar. The Tao is sometimes the Tao and not part of the Jungian system.

When Jung retreated to his tower beside Lake Zurich, he wasn’t meditating ten hours a day as a Taoist might do on a mountain. He was painting, reading, writing, and practicing a visualisation process. Buddhist philosophy describes five skandhas which are aggregates of illusion:

– Form, matter, body

– Sensation, sensory experience

– Perception, mental process

– Mental formations, imprint, conditioning

– Consciousness, discrimination, discernment

Jung’s visualisation method, which he called Active Imagination, fits the third and fourth category. This is the problem with a Jungian approach. Taoism doesn’t fit the skandhas, and nor does the I Ching. Although it is valuable reading. For example, Jung’s foreword to Wilhelm’s book where he uses the term “psychological phenomenology” and Karcher’s Total I Ching: Myths for Change.

In Karcher’s book Ta Chuan: The Great Treatise, he writes about this important part of the Confucian Ten Wings. On the matter of change, he says “The power and virtue of Change is both round, which invites the spirit, and square, which grounds knowledge.”

The differentiation between spirit and knowledge is interesting, the circle suggesting a process which is not fixed while the square rests solidly. We encounter square facts which must be negotiated with knowledge. Spirit is not knowledge because “the Tao that can be told is not the real Tao.” Facts occur within time as the Ta Chuan advises: “The past contracts. The future expands. Contraction and expansion act upon each other; hereby arises that which furthers.”

In the Ta Chuan we read “What is easy, is easy to know; what is simple, is easy to follow.” The first two hexagrams are described as easy and simple. Taoist action flows with a current not against it, and there’s an application here with psychology. Depressed people are told pull yourself out of it, as a lamentable social attitude. It doesn’t help, spoken internally or received from others, but there is a Taoist alternative. The central line of change in the yin and yang symbol is curved not straight. Yin doesn’t usually change to yang without intermediary stages. This involves categories of negative and positive yin, and negative and positive yang.

Sadness is negative yin which needs positive yin. This means encouragement, support, and kindness; building up not cutting down with judgement. Negative yang is aggression which needs positive yang not yin. An unpleasant person perceives yin as weakness. The first person changes to yang when they feel greater confidence; the second realises they can’t impose and must moderate with yin. In their case they need firmness and positive role modelling, so they find a confidence where proving themselves is unnecessary.

Sadness can more easily change into compassion, which leads to gratitude, and then joy. Anger can more easily change into confidence, before compassion. Fear can become awareness, leading to confidence, then competence. Direct change from one opposite to another is unlikely. The Taoist approach emphasises process, not goal, and we read in the Ta Chuan how this occurs with the hexagrams: “As the firm and the yielding lines displace one another, change and transformation arise.”

There is such a thing as drastic change, but it’s unusual. This occurs when “The influences are in actual conflict, and the forces combat each other like fire and water (lake), each trying to destroy the other” for hexagram 49 called Revolution. This is not how we operate in normal circumstances. Sociologically, Revolution is a time of Copernicus and conflict. Something new arrives but others disagree with it.

The fear example of change is interesting, where a person unused to self assertion can learn new techniques (awareness) which facilitate a sense of power and control. This means assertion training, or even Aikido. Practitioners are taught not to fight directly, but redirect and respond on the paradoxical basis of accepting hostile intent. The instinctive reaction is oppose and object to it. A more sophisticated reaction is accept it exists – they want to hurt you – but don’t stand in a location, physically or psychologically, where that succeeds.

Wilhelm describes three forms of change with emphasis on the first:

In the Book of Changes a distinction is made between three kinds of change: non-change, cyclic change, and sequent change. Non-change is the background, as it were, against which change is made possible. For in regard to any change there must be some fixed point to which the change can be referred; otherwise there can be no definite order and everything is dissolved in chaotic movement. This point of reference must be established, and this always requires a choice and a decision. It makes possible a system of co-ordinates into which everything else can be fitted.

The co-ordinates are what Professor Chung-Ying Cheng calls “unity in plurality and plurality in unity” (The Philosophy of Change). This seems a contradiction but it is resolved because one encompasses the other. Change and multiplicity obviously exist. But perhaps, and this is described in the Tao Te Ching, there is a way of being above material nature. In the I Ching there are separate but interconnected hexagrams, one state changing to another, but with a common origin. The visible is the yang, the invisible is the yin.

We ask ordinary questions of the I Ching but the system rests on a philosophy of emptiness and stillness. Wilhelm’s teacher was Confucian and his book is considered part of that tradition. It does however have a Taoist component consistent with his spiritual interests. He explains this in the Ten Wings, makes it poetic in the hexagrams, which is why his book is popular. You don’t always understand it, but sense something meaningful in his words.

Change never stops, linear and circular, but non-change underlies it. The result is order not chaos. The Ta Chuan advises “Heaven is high, the earth is low; thus the Creative and the Receptive are determined. In correspondence with this difference between low and high, inferior and superior places are established.” A problem is relegated to an inferior place so it doesn’t overwhelm you. Psychologically you might have to locate at line five, balancing the lines below.

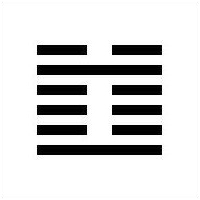

The third I Ching hexagram Wilhelm calls Difficulty at the Beginning. Karcher calls it Sprouting and describes it as “Begin, establish, found; seek a bride; birth pains, massing soldiers; gather your strength to surmount difficulties.” Wilhelm describes the encounter of yang with yin in the preceding hexagrams, which symbolise spirit and matter. The principles are established, then one meets the other. Alfred Huang in The Complete I Ching disagrees with the idea of difficulty, and prefers to call it Beginning. Difficulty does not ultimately have negative connotations. It means life itself is difficult when we incarnate, as the Buddhists say; when we exist in a universe of insecure change.

Karcher, Huang, and other I Ching writers describe the third hexagram in mundane terms. Difficulty means the beginning stage of a project. I Ching meaning is ultimately deeper than any project. The first three hexagrams are where you find the Buddhist philosophy of impermanence, suffering, and the beginning of enquiry.

After heaven and earth have come into existence, individual beings develop. It is these individual beings that fill the space between heaven and earth

– Hexagram 3, Difficulty at the Beginning

I write like this is a magazine column. With research, references, and a lot of time. If you like it, perhaps you would support me.