You should not have any special fondness for a particular weapon, or anything else for that matter. Too much is the same as not enough

– Miyamoto Musashi

The firm and the yielding displace each other, and change is contained therein

– Ta Chuan (Ten Wings)

Miyamoto Musashi is famous for The Book of Five Rings which summarises his samurai philosophy. There are different Ways he says, not necessarily fighting, with the same inner essence. Don’t be fixated with one martial system, style, or narrow approach. Holistic training is the answer, and the same applies philosophically.

I read Nietzsche, Hegel, Husserl, because they stand apart from Western thinking with it’s limited application. I’m not a fan of struggling to understand a page, or paragraph, when the reward is questionable leading to a rabbit hole not the sky. I’m not sure Heidegger is worth reading extensively but he says extraordinary things, based on ancient concepts.

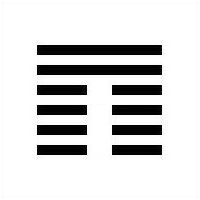

People speak differently with subtly different meaning according to language. English is good at some things but not everything. This is partly a matter of construction but also single words as a constellation of mood and idea. Different terminology is like concept holistic training. Assumptions dismantled, and new understanding emerges. It’s the same with the I Ching. A Chinese system, but with transferable ideas, reconfiguring your understanding of a subject.

My intention is not to precisely define Heidegger, but discover a space of inference and suggestion. In the Japanese tradition there is something called ukiyo describing a floating world with Buddhist connotations of transience and insubstantiality. In his novel Artist of the Floating World, Kazuo Ishiguro connects this with what he calls the “pleasure district” of a city where there are geishas and bars. The concept is however deeply philosophical, described here in relation to pleasure and art:

I was very young when I prepared those prints. I suspect the reason I couldn’t celebrate the floating world was that I couldn’t bring myself to believe in its worth. Young men are often guilt-ridden about pleasure, and I suppose I was no different. I suppose I thought that to pass away one’s time in such places, to spend one’s skills celebrating things so intangible and transient, I suppose I thought it all rather wasteful, all rather decadent. It’s hard to appreciate the beauty of a world when one doubts its very validity.

Aletheia is a Heideggerian term which means revealing or disclosure. He initially used it with an implication of truth, which changed in the course of his work. There is a background of holistic meaning, which is a good description of the I Ching. You can’t find it intellectually, which reflects in the passivity of the definition. It’s there, found when we consult the book; not with habitual linear thinking.

Aletheia is similar to Heidegger’s notion of Lichtung which he describes here in On the Origin of the Work of Art. It means an opening, or clearing, like a lighted space in woods:

In the midst of being as a whole an open place occurs. There is a clearing, a lighting. Thought of in reference to what is, to beings, this clearing is in a greater degree than are beings. This open centre is therefore not surrounded by what is; rather, the lighting centre itself encircles all that is, like the Nothing which we scarcely know. That which is can only be, as a being, if it stands within and stands out within what is lighted in this clearing.

This is similar to Buddhist and Taoist writings, where cognition and perception are designated as limited faculties in relation to a greater whole. There is a constant suggestion in the I Ching of patterns we don’t ordinarily recognise but with meditative focus, and making the time for it, the book reveals. This idea is evident in some hexagrams more than others, for example number 20 called Contemplation:

The wind blows over the earth:

The image of Contemplation.

Thus the kings of old visited the regions of the world,

Contemplated the people,

And gave them instruction.

The notion of a wise ordained king has probably always been suspected even with Pharaohs. The idea is understandable, the reality not, on which basis a king is symbolic. Contemplation in this hexagram means both contemplating and being seen, like a tower with a view of the land. It means philosophy, from which “instruction” is derived, which requires a creatively passive engagement. Carl Jung found The Cauldron (hexagram 50) a useful description of the I Ching, as a repository of wisdom. Contemplation is subtly different, describing the process whereby wisdom is found.

Ereignis means an event in Heidegger’s philosophy, although passively again. Thus something coming into view, implying it exists regardless of perception, much like a hexagram. The well known Zen koan asks the question what is the sound of one hand clapping. In The Sound of One Hand by Yoel Hoffman this is another question:

Master Kyōshō asked a monk, “What is the noise outside?” The monk said, “The sound of rain.” Kyōshō said, “The people are in a topsy-turvy condition, they have blinded themselves in the pursuit of material pleasure.” The monk said, “How about you, Your Reverend?” Kyōshō said, “I can almost understand myself perfectly.” The monk said, “What does understanding oneself perfectly mean?” Kyōshō said, “To be enlightened is easy. To put it into words is difficult.”

The answer is apparent when the monk imitates the sound of rain. It floats, not tied down to the conceptual world; like an I Ching hexagram revealing a moment.

In Tao: A New Way of Thinking, Chung-yuan Chang quotes Heidegger from Existence and Being comparing him to the Tao Te Ching:

Only on the basis of the original manifestness of Nothing can our human Da-sein advance towards and enter into what-is. But insofar as Da-sein naturally relates to what is, as that which it is not and which itself is, Da-sein qua Da-sein always proceeds from Nothing as manifest.

In Heidegger’s Hidden Sources, Reinhard May examines in detail the correspondence between his ideas and those of Chinese and Japanese philosophy. The similarities are clear which leads to the Confucian Ten Wings, I Ching, and Tao Te Ching such as Chapter 40:

Returning is the motion of the Tao.

Yielding is the way of the Tao.

The ten thousand things are born of being.

Being is born of not being.

Japanese samurai were formidable warriors with a social role. When their society changed, and they were no longer needed, they became wandering outsiders with specialist skills. This describes Forest Whittaker in the film Ghost Dog, in which he contemplates a samurai text called Hagakure. There is a scene where poachers have killed a bear, which he objects to, saying “in ancient cultures, bears were considered equal to men.” The poacher disagrees, saying we don’t live in an ancient culture and Whittaker replies “sometimes it is.”

The I Ching provides philosophy and subtlety which Carl Jung recognised as a missing factor in contemporary living. Exotic escape is a false Way if you try to evade real current conditions. The I Ching dates from thousands of years ago but the ideas are not temporally bound. They are culturally different, which is partly what makes them useful.

I’ll conclude with Musashi describing his samurai experience, as advice for more normal living:

Let your inner mind be unclouded and open, placing your intellect on a broad plane. It is essential to polish the intellect and mind diligently. Once you have sharpened your intellect to the point where you can see whatever in the world is true or not, where you can tell whatever is good or bad, and when you are experienced in various fields and are incapable of being fooled at all by people of the world, then your mind will become imbued with…knowledge and wisdom.

I write like this is a magazine column. With research, references, and a lot of time. If you like it, perhaps you would support me.