A tree on a mountain develops slowly according to the law of its being and consequently stands firmly rooted

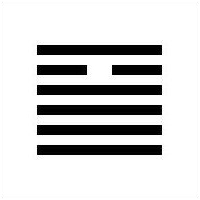

– Hexagram 53

And we laid ourselves down on the empty mountain,

The earth for pillow, and the great heaven for coverlet

– Li Po

The I Ching is an ancient system with different methods of approach. The major division is that between the Meaning and Principle School (yili) and Image and Number School (xianshu). Interpretations vary with different tools. Although for a complex question, or even a simple question, there isn’t necessarily a best answer. It’s like talking with two different people. One person says this, another that, and both are helpful.

For this essay I will describe a system called Wen Wang Bagua which doesn’t use books. Most I Ching users read the books, especially the version by Wilhelm. It’s a literary experience like poetry. An image, such as birds flying across the sky, or a tree growing on a mountain, means more than the literal thing. The tree represents the individual Tao of existence, growing according to its nature. In her book The Living Mountain, about walking the hills of Scotland (my other interest) Nan Shepherd describes water similarly. It’s perfect, powerful, and beautiful on its own terms:

This is the river. Water, that strong white stuff, one of the four elemental mysteries, can here be seen at its origins. Like all profound mysteries, it is so simple that it frightens me. It wells from the rock, and flows away. For unnumbered years it has welled from the rock, and flowed away. It does nothing, absolutely nothing, but be itself.

The value of the Wen Wang Bagua approach lies with the holism of the method. A tree image, or water like the flowing Tao, might be relevant for a question but the meaning consists of various details. The five phases (elements) of Wen Wang Bagua express different relationships such as parents, peers, superiors, descendants, and partners. The ultimate answer to your question is possibly the same, whatever system you use; but there are different ways of arriving there.

With literary training you understand how a poetic image seems simple, but with layers of interpretation. A tree growing on a mountain needs healthy roots, good soil, adequate water and nourishing sunlight. It grows there and nowhere else because of habitat preference. There are lines for hexagram 1 which expand this idea and could summarise the entire I Ching: “The clouds pass and the rain does its work, and all individual beings flow into their forms.”

I Ching imagery captures the meaning of a situation, while Wen Wang Bagua evaluates the structure. Society is not one homogenous thing, individual people are complex, so a question usually involves multiple factors. Even simple answers rest on a sophisticated understanding of psychology, politics, or perhaps health, and are thus holistic.

Crossing the road is a similarly complex process. We can’t do it easily or simply with an instant decision. We look in both directions, evaluate if a space in the cars is sufficient based on speed, traffic, the possibility of another car entering from a side road; watching out for the cyclist who won’t kill you but is still dangerous. In an emergency situation, a team of expertise is needed for a complete not linear response. Bleeding in several places must be stopped, blood clots prevented, shock treatment applied, concussion monitored, and a warming blanket provided.

The eight trigrams represent different energies, moods, spatial and moving directions. Water flows horizontally with a downward impulse. Fire rises up. The trigram system is separate from the five phases of philosophy and medicine (misleadingly described as elements) although there are connections with the same shared principle. Something starts, grows, continues, flourishes, then fades. The phases have different qualities such as initiating, nourishing, and maturing. The five phase system has a direct correlation with physical experience and psychological reality corresponding to internal organs, seasons of the year, and a cycle of emotions:

| Wood | Liver | Spring | Anger |

| Fire | Heart | Summer | Passion |

| Earth | Stomach | Late summer | Worry |

| Metal | Lungs | Autumn | Sadness |

| Water | Kidneys | Winter | Fear |

There is a Chinese Wuxing (five phase) painting school where brush strokes relate to the elements producing different forms of art. Strokes can be light, strong, fast, slow, curved, vertical, branch-like or solid. Wuxing analysis can be applied to different art cultures such as Greek, Japanese, or Art Nouveau. Music, hobbies, food and exercise correspond to the elements so you may like classical or rock, swimming or walking, curries (Metal) or a salad (Wood). The elements have medical implications for acupuncture and practitioners ask diagnostic questions about food preference and energy during the day, because the phases correspond to different hours. The suppressive effect of allopathic drugs is achieved with something called the controlling cycle where fire burns wood, earth contains fire, fire melts metal, and water extinguishes fire.

This comprehensive subject connects with the I Ching in the form of Wen Wan Bagua methods. You don’t read the books but work directly with hexagram structures, lines, and correlations. The written I Ching is philosophical, with Wilhelm in particular and the Confucian tradition. The Wuxing or Wen Wang Bagua I Ching is diagnostic and Taoist. The first is mostly how the I Ching is understood in the West, while the second is popularly used in China.

Some people say the I Ching is a book of divination, while others say it’s philosophy. But the differences are not important when you go deeper into the subject. There is a meaning in the five phase system, as there is with the poetic imagery of a tree. The tree corresponds to the wood phase which means expressing growth, spring, and free expression which when blocked or frustrated becomes anger. A divination reading expresses philosophy, and philosophy applied becomes divinatory.

The yili and xianshu traditions developed separately but are ultimately complementary. Early philosophy was attached to the I Ching in the form of yin and yang theory and the five phases. Later philosophy was attached when sophisticated people (Wilhelm in particular) studied the book, read ancient writings, then wrote themselves. There are differences between Taoism and Confucianism, but this is irrelevant for the pursuit of useful veracity. Bruce Lee had the same idea about martial arts. He described competing styles as “cults” and advised “Absorb what is useful, discard what is useless and add what is specifically your own.”

Richard Kunst in his PhD dissertation The Original Yijing (1985) describes Wilhelm and James Legge as missionaries interested in the intellectual world of Chinese scholars. This is correct, but grand-daughter Bettina Wilhelm notes in a film she made about him how he had interests which were not merely scholarly. There is a comparison here with Carl Jung who studied alchemical texts partly but not entirely for intellectual learning. The imagery, he found, had psychological significance for his work. It’s the same with I Ching hexagrams.

There are trigram references in Wilhelm explaining his yili text, and where it is based on xianshu. For example with hexagram 14 “The two trigrams indicate that strength and clarity unite” and “The two primary trigrams, Ch’ien and Li, are both ascending, and so are the nuclear trigrams, Ch’ien and Tui. All these circumstances are extremely favourable.” In summary, Ch’ien and Li designate strength, action and positivity combined with clarity and productive relationship. The direction is upward, reinforcing the meaning. Ch’ien and Tui internally (nuclear trigrams) means the same for the first, combined with relaxed happiness for the second.

The implication of these references is profound. Wilhelm uses xianshu, and his book is the result. It’s not always apparent, and he adds another layer of philosophy; but the structural basis is there. This information is found in the third section of his book, not the first, for which the usual advice seems incorrect. People say the first section is the text, and the third section is interpretation, and the first is best emphasised especially for beginners. It is true the additional information in the third section is potentially confusing. But where it is explanatory, referring to line relationships and trigrams, this is the heart of the I Ching and correspondingly valuable.

Wilhelm’s book is not the Wen Wang Bagua system but at the end of it he provides the Eight Palace arrangement of hexagrams, with no explanation, which is fundamental for Wen Wang Bagua. The Eight Palaces were designed in the Han dynasty by someone called Jing Fang. The diagram is the basis for divination rules which some people are say are too rigid, but within the rules flexibility of meaning applies.

The five categories of parents, peers, superiors, descendants and partners can mean simple relationships or be subtly inferential. Parents for example can mean the originating basis for a project, people of indeterminate number, or an initiating idea. The system is outlined in An Anthology of I Ching by Sherrill and Chu and The Authentic I Ching by Wang Yang and Jon Sandifer. They describe related meanings whereby romantic partners for example can also mean money and business. How one is similar to the other is part of the intuitive process in the same way a tree image is poetic.

Wen Wang Bagua appears to be practiced more as fortune telling than for increased awareness Wilhelm and the yili tradition encourages. This was possibly not the original intention. What usually happens is teachings become diluted as they pass down through time. We inherit the rules but not the spirit of early I Ching practitioners who were part of a different culture with a greater connection to nature.

There are still layers of mystery and the unknown within I Ching culture. It would need someone like Wilhelm, living in China, with access to an authentic tradition, to clarify Wen Wang Bagua methods. Meanwhile the rules are provided, and we can work with this comprehensive system, especially if we are familiar with the five phases of wood, fire, earth, metal, and water.

I write like this is a magazine column. With research, references, and a lot of time. If you like it, perhaps you would support me.