The Tao is an empty vessel; it is used, but never filled

The shape changes,

But not the form

– Tao Te Ching

I’m constantly reading Richard Wilhelm’s I Ching and advise people to do so. You must however understand what it means. He wrote poetically and philosophically, not directly for you and your question. You find correspondences, which are useful, but it’s a general manual more than a collection of answers.

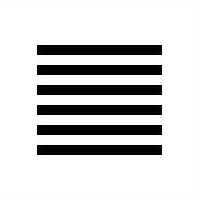

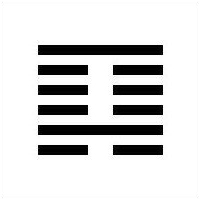

You have to make the I Ching your own, not with random rumination but working with structures and symbols. The question I examined here is “why is the I Ching now in my life?” The answer he received was the first hexagram.

This is an example of how I read the I Ching for a question and compose an answer. It’s structural, using lines and trigrams, which I will explain.

At one point in Wilhelm’s book, he wonders if trigram ideas were the original I Ching method. This can be misleading, because earlier is not necessarily better. It does however affirm the trigram structure approach. Although not reading the books, which is what this entails, doesn’t mean you only focus on trigrams.

Carl Jung once asked the I Ching to describe itself and the answer he received was hexagram 50 The Cauldron. His question and that specific hexagram connects with the situation of “why is the book now in my life.” Everyone understands the I Ching is a book of advice, or wisdom, so that is implicit in the question. That could vary however depending on the person. It might be a doubtful question, which changes the context. You could then receive an answer like Youthful Folly.

I was surprised with hexagram 1 because there are others you might think appropriate. Hexagram 50 for example, or possibly hexagram 48 called The Well. But that is not how the I Ching works, with formulaic understanding. Answers and advice are often unexpected and surprising. I compare I Ching readings with what poet John Keats called negative capability: “being in uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

If you knew the answer, you wouldn’t need the I Ching. There must then be a fundamental understanding that you don’t know, like the yin unconscious alongside the yang conscious. It’s important to consider all these details in an I Ching reading, as the bigger philosophy, because they are where the question locates. You ask the I Ching why are you now in my life, and the book answers with the full system as it did for Carl Jung.

The other reason why I was surprised with hexagram 1 is because it’s not a common occurrence, and there is a certain thrill with six yang lines. The dragon enters the room. Wilhelm’s book describes a dragon in six stages of manifestation as the yang power of the universe and where the I Ching begins.

Consistent again with Jung’s question and answer – and this is where it becomes divinatory in regard to the question – the first hexagram delineates I Ching function as a process of six lines, or six stages, beginning then fading at the top. This repeats in hexagram 31, sometimes regarded as the beginning of the second section of the I Ching.

Consistent again with Jung’s question and answer – and this is where it becomes divinatory in regard to the question – the first hexagram delineates I Ching function as a process of six lines, or six stages, beginning then fading at the top. This repeats in hexagram 31, sometimes regarded as the beginning of the second section of the I Ching.

I suspected the questioner had wondered about the I Ching for some time, the attraction was not strong enough, but now it is. That can be mapped onto six stages, not as a technically precise proposition but as a general principle. In other words he had an early beginning interest, then it faded a little, then it returned. Like the dragon waking, then wondering if he should act, depending on the time.

The time is now for the I Ching in his life. It will be an important resource and the book affirms his interest very strongly. There is no stronger hexagram, albeit strength in the I Ching is not always what you expect. Soft water can be stronger than hard rock. Gentle influence is sometimes more effective than loud assertion.

The first hexagram does however emphasise the idea, or principle, and this is an important factor for early I Ching discovery. There’s always an element of doubt and uncertainty. How does it work, and what does it mean, because it is not a widely known subject.

If there were no moving lines in the answer, that would be perplexing until you think about it more deeply. What does unmoving yang have to do with I Ching interest? The point about interpretation is it can be very subtle. If a hexagram or an image has seemingly no relevance for a question, deeper meanings arise. It might be the idea you have about a question, which is not actually correct. So you don’t receive an answer as such, but are told to think about it more deeply. Jung called the I Ching “psychological phenomenology” for good reason.

This is why I use prolonged reflection for answers more than immediate discussion. You must talk to the person, see them, get a feel for them, either in real life or online. The interpretation for me then takes a long time, spread across a few days, as I ponder the details and meanings. There are always immediate impressions with a hexagram, which can be shared, but it’s not ultimately an immediate process.

If it were an unchanging yang for the question, he would have to consider his ideas about divination generally. Is the yang in the system, is the yang in him, and what is his understanding about the idea of yang? In addition to obvious commentary, an I Ching reading gives people philosophical tools from the wider system.

Six yang lines are statistically unusual and conceptually strong so the I Ching is saying: what is your understanding or experience of yang? For the I Ching yang means spirit, order, creativity, male, and light against darkness. How do these connect to your life? Some parts of a reading are obvious while others can be background, hidden, or subsidiary details.

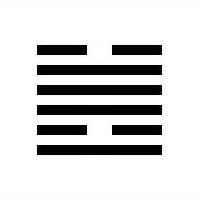

There is thus a yang context as the starting point for interpretation. Within which there are two moving lines, the second and the sixth, which is where you can examine the subject more deeply. The second line changing to yin becomes receptive to the yang line in the fifth place. The fifth line is usually the ruling line, like a king in a kingdom, subordinate only to the sixth line of the priest or sage. He has the manifest power but not the entire wisdom for his kingdom, himself, or his subjects below.

Being receptive to the fifth line equates with listening to the I Ching. The fifth doesn’t have the ultimate wisdom of the sixth but no one can question him from below. It’s strong again, as yang, illuminating the darkness of yin. The upper trigram is other and the lower trigram self, so in this situation the I Ching is now entering his life. In the developmental process of six lines, the second is now becoming yin at this particular moment. He’s wondered about the I Ching before, but didn’t do anything about it, which meant he couldn’t receive the information from the fifth line king.

It’s the centre line of the lower trigram which is the inner principle of self in relation to (in this case) the organising principle of a higher function. He is now receptive. That answers his question very directly – why now – but there is more to consider with the I Ching when every detail connects with the wider system.

It’s a yang hexagram, with two lines becoming yin, which implies the Taoist philosophy although not confined to this or any other hexagram. This is not always an interpretive beginning but is, in this case, because of the quality of the first hexagram. Dragon enters the room: the I Ching knows its own power.

The upper line is also changing to yin which again means being receptive to wisdom. The yang dragon of the sixth must beware of arrogance. There is a progression from first to sixth we construe as development and advance in terms of a project, goal, or accumulating wisdom. The sixth line is the sage, retired from society because he doesn’t need it; but as a Bodhisattva principle he must return energy down to those less wise or experienced below. It’s not a command, and you are free to choose otherwise, but with inferior consequences.

There are yin and yang demarcations in the I Ching, just as there is a positive and negative in an electric circuit. But it’s layered, and what appears to be success at one level might be unfortunate above. This is the area of ethics, conscience, and what Confucius called ren which is basically kindness and benevolence. The acknowledgement of levels applies in the hexagram as three groups of two lines: heaven above, earth below, and humanity in the middle.

The sixth line dragon is ultimate, except not quite, representing the idea that even the I Ching is not infallible or always needed. There are some questions it’s best not to ask. I know this from experience, in relation to serious concerns where you need stillness and quiet yin, more than interactive questioning yang. You might need a few days, a week or more, before you can approach the I Ching because the time isn’t right for it.

The Heaven hexagram is thus instructional for him in regard to his recent I Ching interest and how to understand the relationship between human being and book. People describe the I Ching like it’s a conversation with the Sage. You can understand this as dialogue with the unconscious, the Jungian approach, where you access a deeper layer of knowing.

I am wary of jumping into the details of a changed hexagram derived from moving lines. What usually happens is there is a great depth in the first hexagram which must be explored. A moving line is activated yin or yang, but can be contained. It’s an excited line like anger, desire, or another impulse, not always favourable or advisable to express.

The meaning of a second hexagram is also debatable. It’s commonly understood as an outcome, which then overshadows the first making the variables into something certain. An outcome can be a resolution, or possibly a warning, depending on the question. There isn’t a correct answer to this and what happens with the I Ching is to some extent, you define the system for yourself. Your unconscious works with whatever framework you decide upon.

The two changing lines in the reading are for his consideration in regard to lower self in relation to higher wisdom seen with yang becoming receptive yin. There are readings where a potential second hexagram, derived from changing lines, becomes immediately useful. I don’t think this is one of them. There’s a danger you think in terms of fortune telling and this is what will happen, contrary to I Ching philosophy.

Remaining with the first hexagram of Heaven, the two Heaven trigrams are changing into Fire and Lake respectively with two considerations. Firstly, the trigrams repeat my line analysis. Secondly, this part of the reading is a summary of my advice with simple imagery for him to remember and apply.

The meaning of Fire is clarity like shining a light into darkness. The I Ching provides clarity. This occurs in the lower trigram of self in relation to the upper trigram of other which in this case concerns the I Ching. The upper trigram is Lake, which is a receptive principle because of the upper yin line. He is illumined below from the trigram above because of two changing lines occurring now.

Interpretation for me can’t be instantaneous, because of complexity and subtlety. I write my readings, because some ideas can’t easily be conveyed. Additionally, it’s very valuable having the information carefully composed and arranged. Conversations vanish but written words do not.

If I said for example the trigrams for this question relate with a quality of Wind, it wouldn’t mean very much. The term for this is Resonance and needs explanation. In a hexagram these are corresponding lines:

- the first and the fourth

- the second and the fifth

- the third and the sixth

They might relate harmoniously or not, which is another layer of meaning. The second changing line is important in this interpretation in relation to the fifth. Additionally, you can consider the Resonance trigram using all three connections with the following rules:

- both lines are different, the result is a yang line

- both lines are equal, the result is a yin line

A trigram then emerges which explains the relationship between the lower and upper in the hexagram. In this case it is Wind advising a gentle divinatory effect, not the yang of the hexagram which is the immediate impression. The advice is about the approach he should consider when using the I Ching. Gentle, flexible, and suggestive more than definitive.

This is particularly important if you read a book, Wilhelm’s or any other, which are poetic more than mantic. “It is good to have somewhere to go” for example can suggest taking a holiday, daily work in the office, or walking in nature. It can also mean psychological readjustment and changing your outlook from one trigram to another.

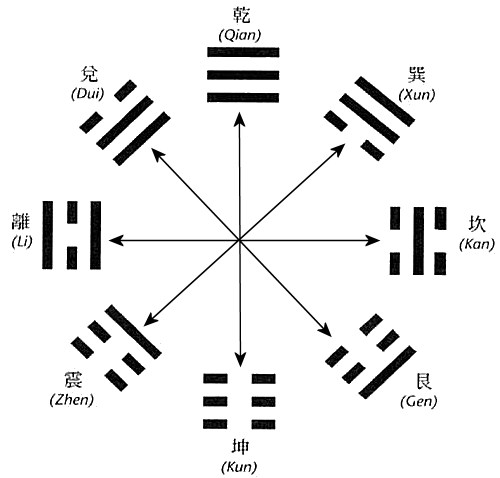

Kan means Water and the Abysmal as hidden depths but also danger. It might be depression, when you can’t see and thereby change the energy of a situation. Move across to Li, Fire, and you find the Clarity you need. Dui means Lake which is a happy disposition but not properly considered. Gen, the opposite, is the meditation of Mountain where you contain and examine your feelings. Emotions and circumstances can be mapped onto the Ba Gua and remedies considered.

The I Ching system is a philosophy and collection of principles which should be applied flexibly. The hexagrams assume a dynamic world with multiple dimensions, enfolded in the fabric of reality. The notion of change underlies this, which is a simple but also complex idea. There are different kinds of change like hard and soft, sudden or prolonged, vertical or horizontal, inside or outside. The quality and energy of change can itself be examined with something called the Change Operators.

The Inner and Context Operator describes the inner disposition and place of change. It might be at work, home, within a group, or set of ideas. This applies throughout the I Ching, where a context can be material or otherwise. The hexagram is obtained by defining a yin line where change is occurring (the moving lines) and a yang line for those which are static. This is all that matters: the quality of changing or not changing.

The Outer or Energy Operator describes the actions through which change occurs. This is defined by placing a yang line where change occurs, and yin where it is static. For hexagram 1, with the second and sixth line changing, these are the Context and Energy hexagrams:

| Context Operator 49 | Energy Operator 4 |

|

|

The first is the same as the derived hexagram commonly used (if you changed the moving lines in this reading) which is Lake over Fire hexagram 49 Revolution. This can be examined, certainly can’t be dismissed, but I’m going to emphasise the second. Mountain over Water is hexagram 4 Youthful Folly.

It’s possible to consider these hexagrams in terms of lines and trigrams consistent with the process above. I will do this briefly, because at this point there is a danger of too much information. This is part of I Ching analysis, where you identify and balance what is important in relation to lesser importance.

Mountain over Water means reflection in relation to emotions and the unconscious. Water flows with its own volition both creatively and destructively. If you manage it carefully, it vitalises and enlivens. If you don’t understand it, water floods and destroys. You see this in the character of young people, with desires and aspirations they don’t understand because of inexperience. A good example is the character of Jen Yu in Ang Lee’s film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

Hexagram 49 concerns change, and hexagram 4 is the beginning of a project or interest. It’s a learning phase when we don’t know, like the scene where Li Mu Bai teaches Jen Yu as they duel in a bamboo forest. She struggles with balance while he is relaxed, watchful, and composed.

Youthful Folly can be negative if you are an adult making mistakes. But it also means the age or phase when you develop understanding through experience. It can be a warning, advice, or a simple observation about I Ching or any other learning.

The I Ching is generous. It explains why the book is now in his life, and describes the process as the basis for future reading. This occurs within the structure of yang like a battery, or electrical circuit, from which future energy derives.

There is, sometimes, a vague approach to the I Ching missing the essence of the system. It’s like 1960 hippies turning on, tuning in, and dropping out with substances and Eastern philosophy they didn’t actually understand. It was more a counter cultural fashion than the deep exploration of another.

The I Ching expands understanding, as a deepening not an escapist process. Trigram study is part of this, because it’s not superficially found. Start with the Shuo Kua in Wilhelm’s book, which is where the eight energies are described. The yang principle is a reminder that although yin is required – you must be receptive – that doesn’t mean abdication of responsibility and reason.

Reason is found in philosophy, although the Chinese context is different from cerebral Western practice. As for example with the five elements or phases, which can partly be summarised as a grounding in nature, then the changes of energy, like autumn becoming winter then spring.

Heaven is the first hexagram, suggesting the beginning of an I Ching journey. Sixty three hexagrams remain, although as the years pass you experience the system not as a linear path but as unexpected unfolding discovery. Yang light illumines the dark yin unknown.

I write like this is a magazine column. With research, references, and a lot of time. If you like it, perhaps you would support me.